the Yamaha Integrated System

Some notes on Yamaha's 1982 visionary computer

In the early 1980s, the Japanese domestic market for personal computers was dominated by NEC, the PC-8001 accounted for nearly half of it in 1981. By 1982 many other Japanese manufacturers were working on competing computers, such as Sharp with the MZ-80B, Fujitsu with the Micro 8, or Canon with the CAT-1. Foreign companies such as Apple, Commodore, Sinclair were trying to enter the market as well. As Yamaha was already capable of producing custom chips and integrated circuits, creating a personal computer was a logical move.

This is the story of the YIS, the Yamaha Integrated System: a personal computer with lots of interesting peripherals that ultimately was too much for the early 1980s and disappeared into obscurity in less than 2 years!

At that time, Yamaha was the second largest company for in-house production and consumption of integrated circuits, after IBM. They were already capable of producing highly complex chips (LSI, or Large Scale Integration circuits, containing up to 10000 transistors in the same package) used for musical instruments. Much of this is thanks to Yasunori Mochida , who during the 1970s was already pushing for digital processors capable of producing sounds, a research that with the collaboration of the famous professor John Chowning would later result in the first mass-marketed digital synthesizer: the DX7 . Mochida was appointed managing director of the YIS project, as years of LSI development were finally reaching the market.

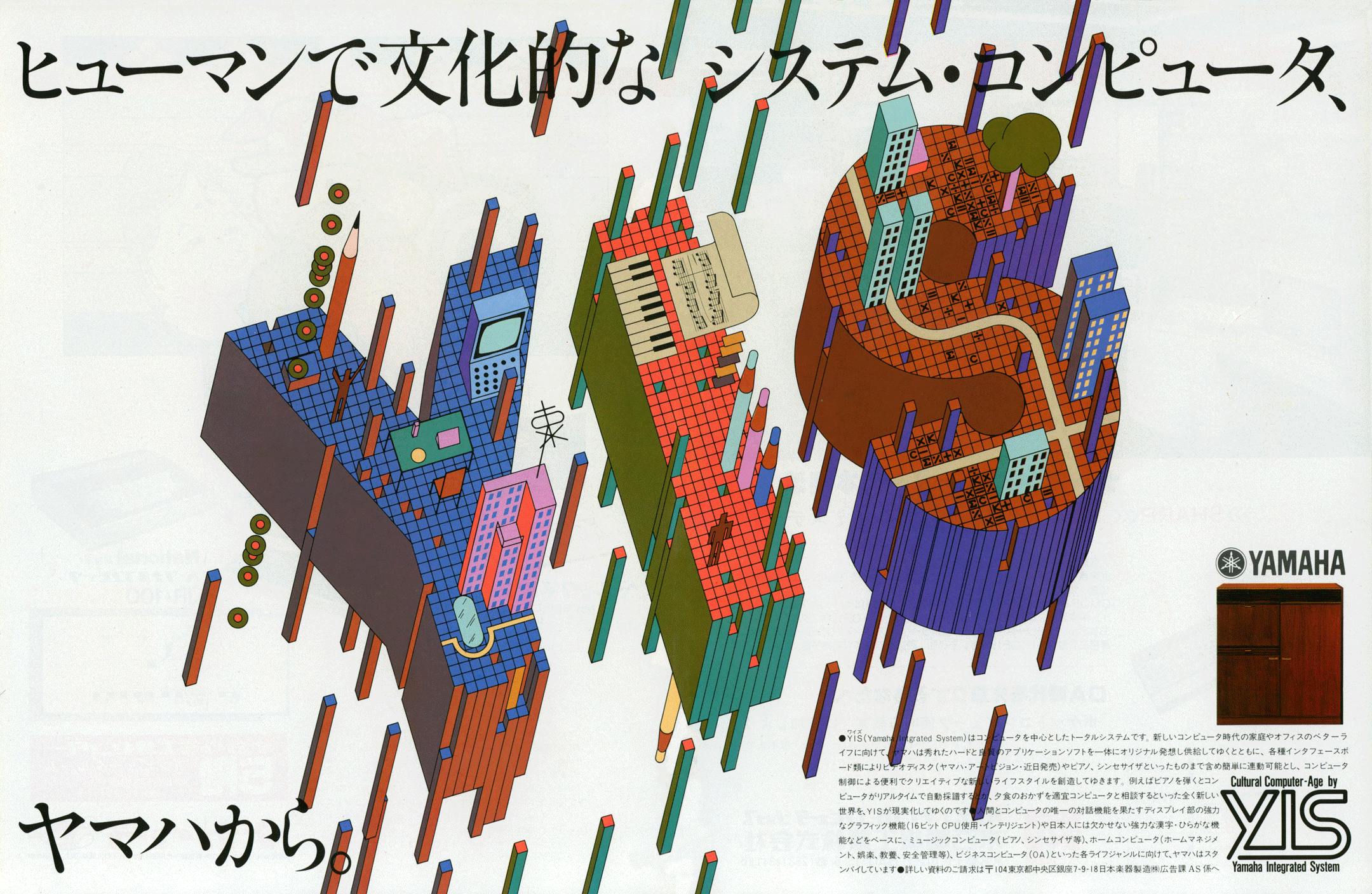

Allegedly, Yamaha held a press conference in December 1981, opening its first shop (more on those later) on December 12, 1981. No actual proof of this press conference could be found. However, Yamaha’s first public announcement of their ambitious new plan happened in January 1982, when they purchased a double-page advertisement on ASCII, the official publication of the homonymous organization (“a monthly magazine of home and office computer science”).

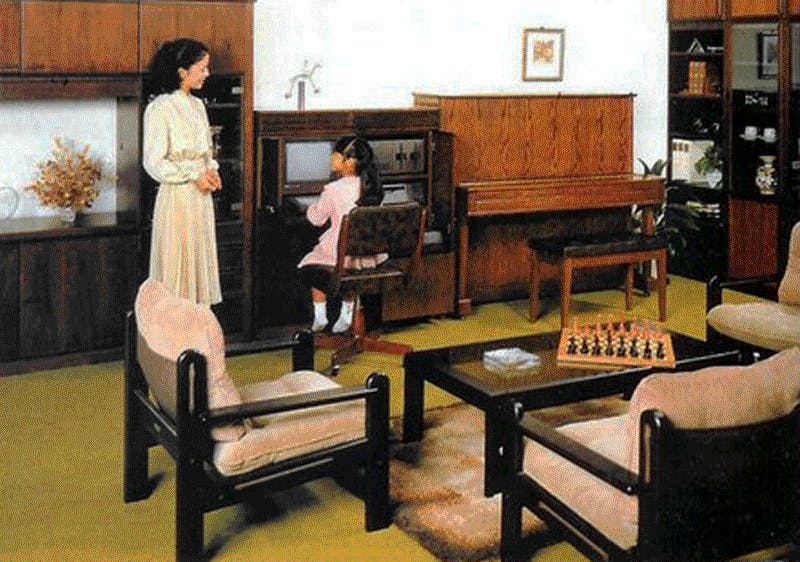

The illustration is likely by famous Japanese designer Takenobu Igarashi, although he’s not credited anywhere. The text explains that the YIS is a total system centered on the computer, best for homes and offices in the new computer era. Yamaha pledged to release excellent hardware, useful software, and various interface boards. “A new lifestyle, convenient and creative”, that includes for example being able to play the piano and see the computer transcribe the notes in real-time, or “new ideas” such as consulting the computer about side dishes of a meal for dinner. In the bottom right corner, a sort of wooden cabinet, still closed, holds the promise of a future where home management, entertainment, culture, music all happen around a personal computer.

A more in-depth introduction can be found in February 1982, as ASCII dedicates a full article on the new system. This is supposedly the month the first computer (the PU1-10) went on sale. It’s described as a modular approach to domestic computing: the computer could be used alone, but its capabilities could be infinitely expanded with peripherals and expansions. A table in the article lists the computers and all the extensions already available:

- Central processing units ( PU1-10 or PU1-20 ), a computer built on the YM2002 processor with two floppy drives and 64KBs of RAM.

- Video displays ( GM1 or GM2) that could also be hooked up to a custom VHD player.

- Computer keyboards ( KB1 or KB2) available with mechanical keys or membranes.

- A dot impact printer (PN1)

- A piano control unit ( PC1 ), a piano interface (PU1-BP), and its custom sensors to hook up to an existing piano (PL1) to transform key presses into digital data or vice versa to automatically play the piano from a digital recording.

- A music keyboard ( MK1 ) with an unknown kind of FM synthesizer interface to be plugged into the computer (PU1-BM).

- Lots of walnut/teak furniture. A cooling fan could also be installed in the main computer cabinet.

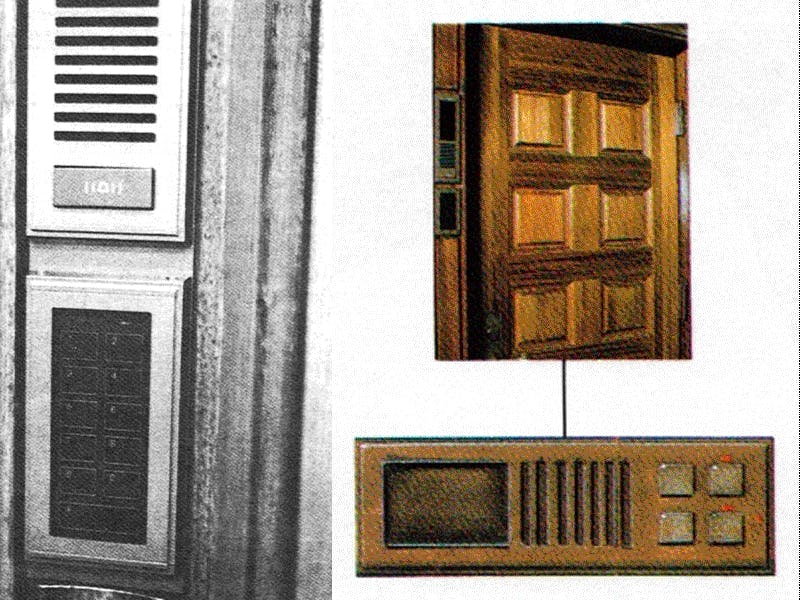

An advertisement a few pages before also shows a bigger roadmap Yamaha had in mind to further expand the system. Two kinds of VHD video players (DP1 and DP2) dubbed Yamaha Art Vision, a doorbell with an integrated camera, a room unit that likely contained a temperature sensor, and some kind of link to the Electone family.

Scan by yamahablackboxes.

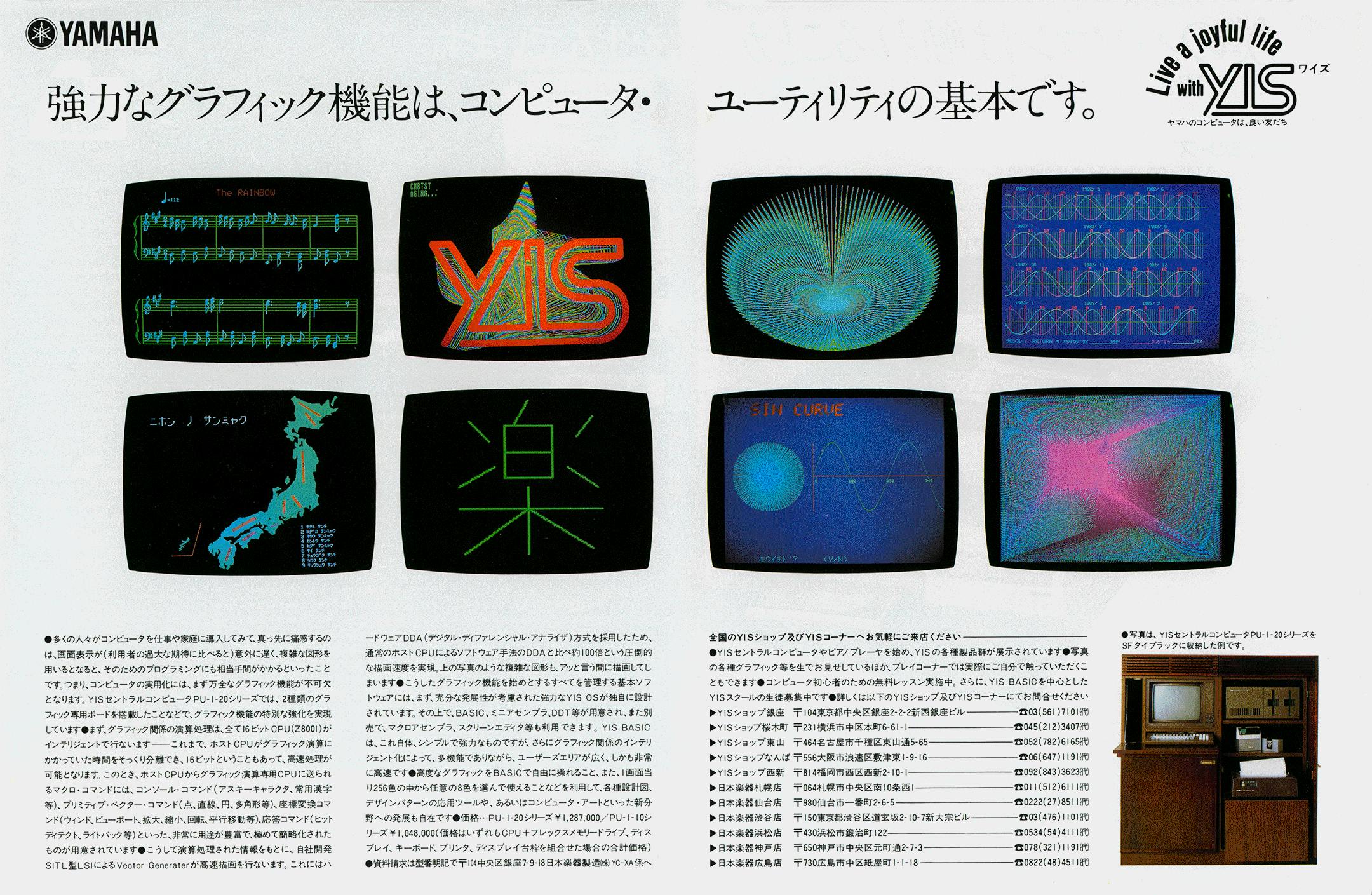

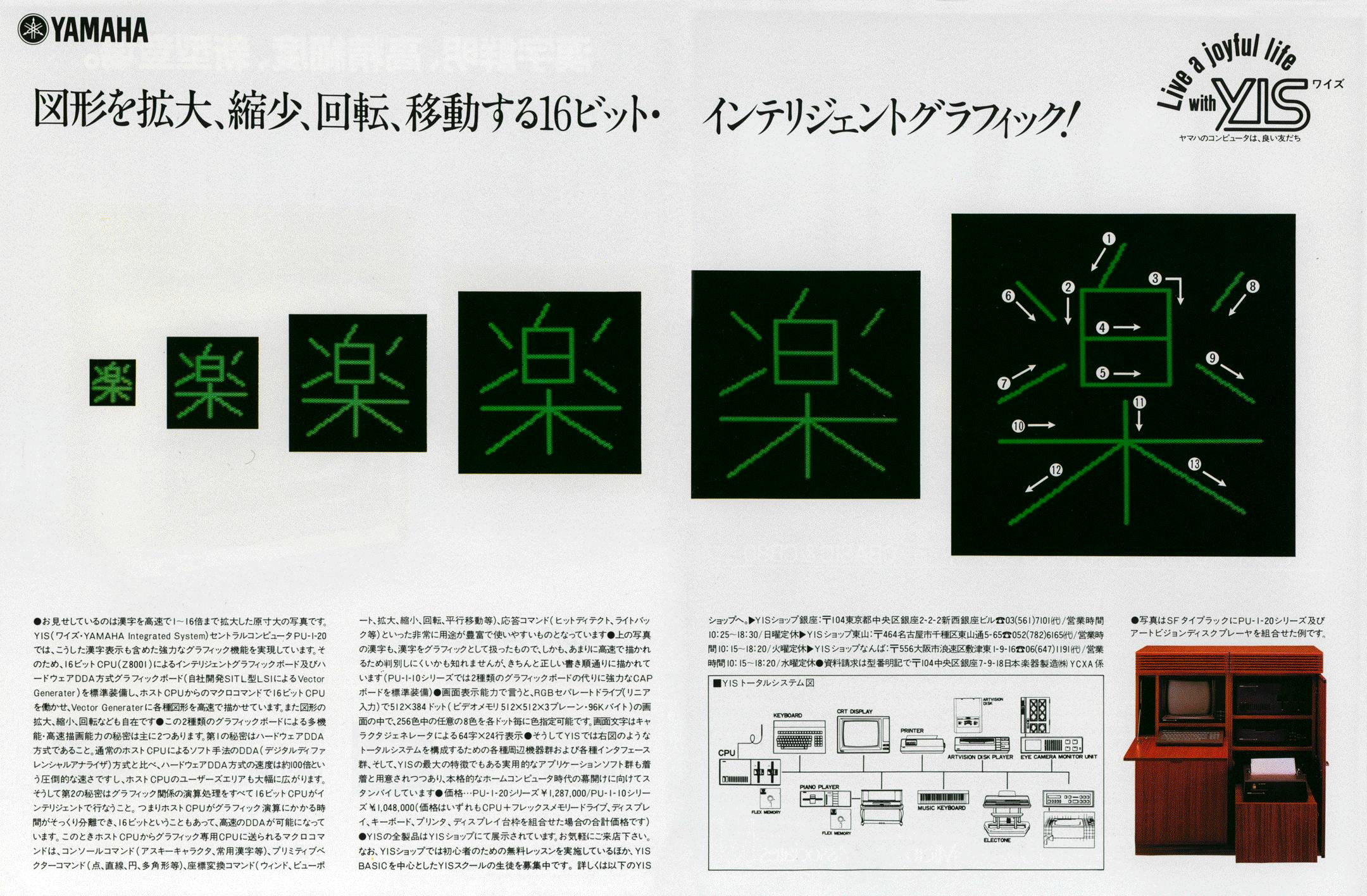

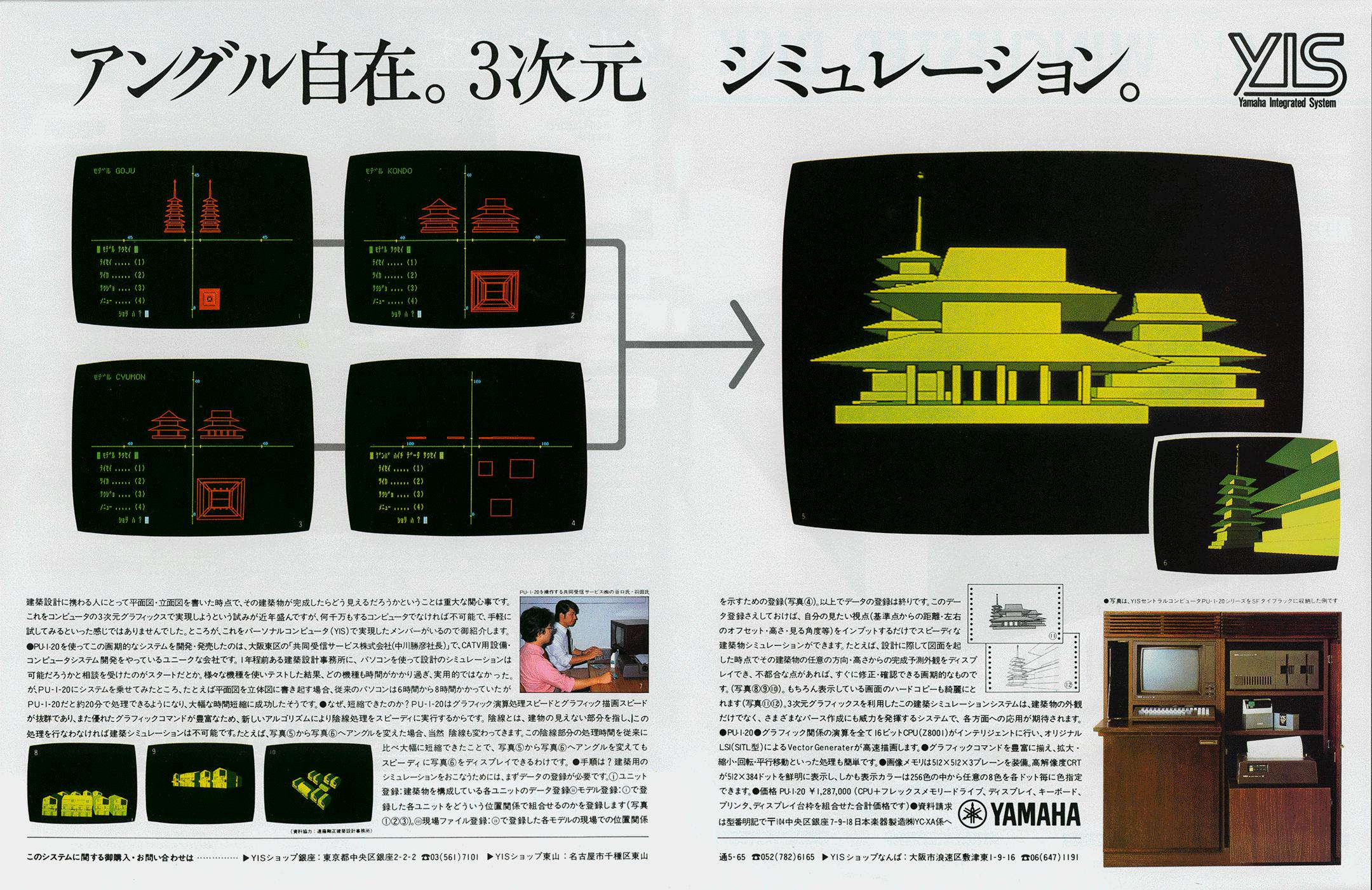

In the following months, Yamaha proceeded to advertise the innovative graphical capabilities of the YIS operating system. No other 8bit personal computer at that time was able to perform such complex visual operations: the Yamaha computers had a dedicated board to process high-speed drawings. This board used a proprietary LSI announced by Yamaha in November 1981 that could perform DDA processing (Digital Differential Analyzer) at a hardware level. This method was said to be 100 times faster than competing computers that used the CPU to do all the heavy-lifting, while also of course freeing up computing resources (not far from the way microprocessors and graphic cards are separated today)

The output resolution was 512x384, with the ability to pick 8 colors from a palette of 256. Lots of versatile graphic commands were available to programmers: primitive vectors (points, straight lines, circles, polygons), coordinate conversions, windows, viewports, sprite functions (scale, rotation, translation). Even if some operations were implemented as vector calculations, the board wrote screens to an internal VRAM that was then read line by line by a monitor (so the result is always a map of pixels). The VRAM has 96KBs available so it can hold 3 planes at 512x512 pixels.

Apparently, the GM1 could also superimpose computer graphics and an external NTSC video signal. It must have been very futuristic seeing the video feed from the doorbell next to some kind of information coming from the computer. Some of the graphic capabilities of the YIS wouldn’t be available on personal computers for years — Windows didn’t have system-wide hardware acceleration support until Vista (2007!).

Yamaha wasn't selling "just" a personal computer like the competitors. Live a joyful life with YIS. This whole new lifestyle could be experienced at 11 YIS shops around Japan. It’s hard to trace back the actual history, but Yamaha here probably pioneered the Apple Store concept. Tokyo, Yokohama, Nagoya, Osaka, Fukuoka, Sapporo, Sendai, Hamamatsu, Kobe, Hiroshima: no other competitor in 1982 had such a network of first-party locations.

Such shops had a full lineup of YIS products that could be freely tried by the public. A piano was also available to test the piano player features. There were free seminars for beginners, but the advertisement also mentions a school where students could learn more about the YIS Basic programming language.

If you’re curious this is the corner with the first Yamaha store in Tokyo, although the building has probably been demolished and rebuilt since the early 1980s. Yamaha’s main shop is actually still located in Ginza, Tokyo, not too far from that old location.

We don’t know if any of the home automation products were available in shops. Prototypes did exist at least by the second half of 1982: a Spanish magazine in October 1982 reports the existence of a door system with an electronic key, numeric pad (with DX7-like membrane switches) to input a passcode, and an infrared camera that could store a picture on the central computer in case someone rang the bell while the owner was away. The same magazine also briefly presents the possibility to manage the temperature level of the bathroom via a Yamaha appliance linked to the YIS computer, but doesn’t show any pictures.

Scan by yamahablackboxes.

Some advertisements focused more on the professional applications of the YIS central computer. For example, there was a lot of interest from architectural firms towards having simpler ways to show how a building could look like, starting from the floor plans. When rendering a solid object the complex part is calculating the hidden lines, and the PU1-20 was said to perform in 20 minutes an action that could take up to 6-8 hours on other computers. The CAT software programmed by a company called Kyodo, in Osaka, also allowed to make prints of the resulting 3D model. For this kind of application, the light pen that was also available for the YIS was likely very useful.

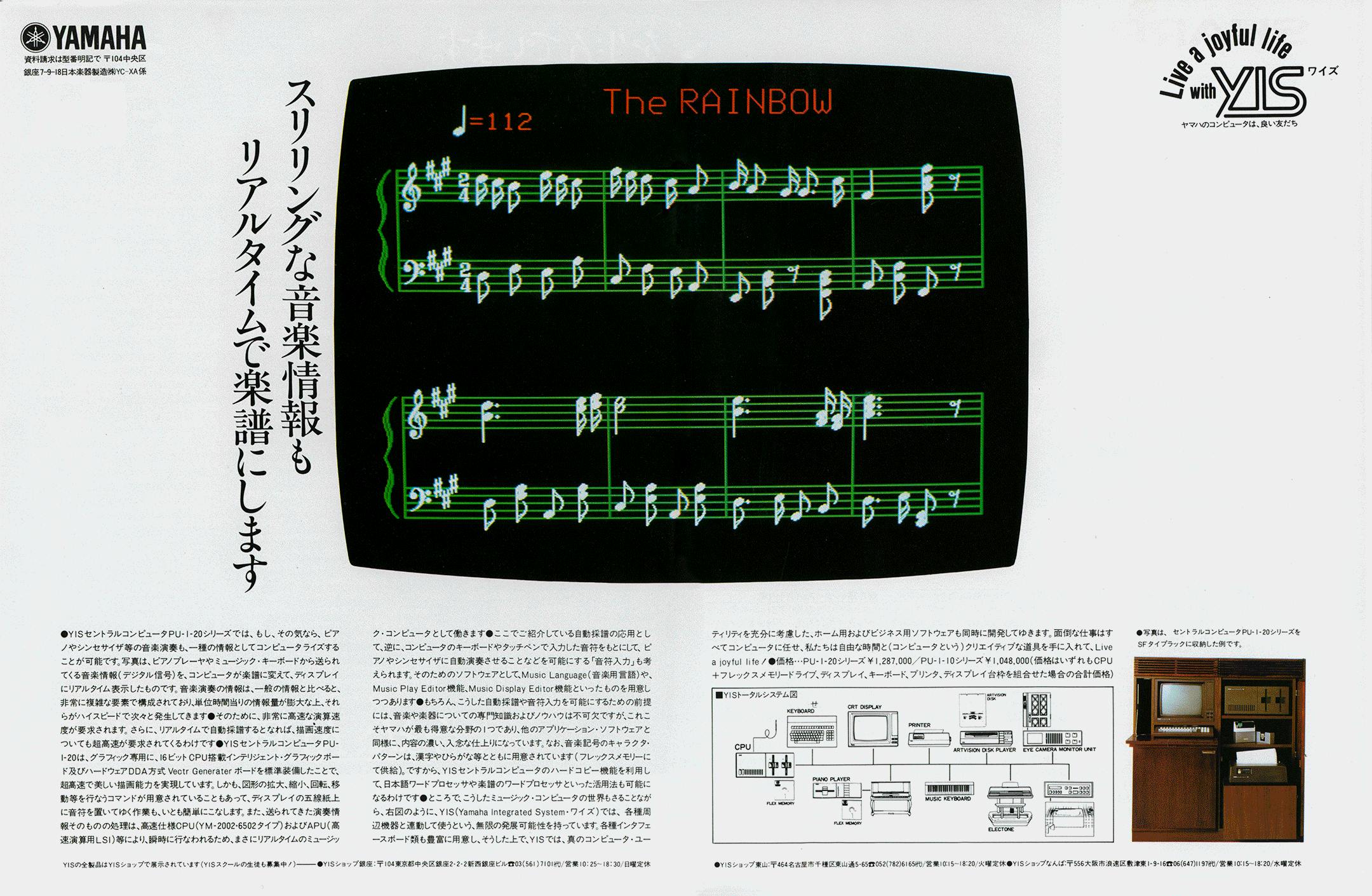

Finally, music was the other big selling point. The first use case was digitizing piano performances: the PC1 was able to communicate with the central computer to store the recorded performance in digital form. The user had then the ability to store it on a floppy disk, print the sheet music, or play it back (seeing the keys move automatically on the piano). This technology predates MIDI but it remained one of the core businesses of Yamaha even after the 1980s: today this sort of functionality can still be found in Yamaha’s Disklavier pianos.

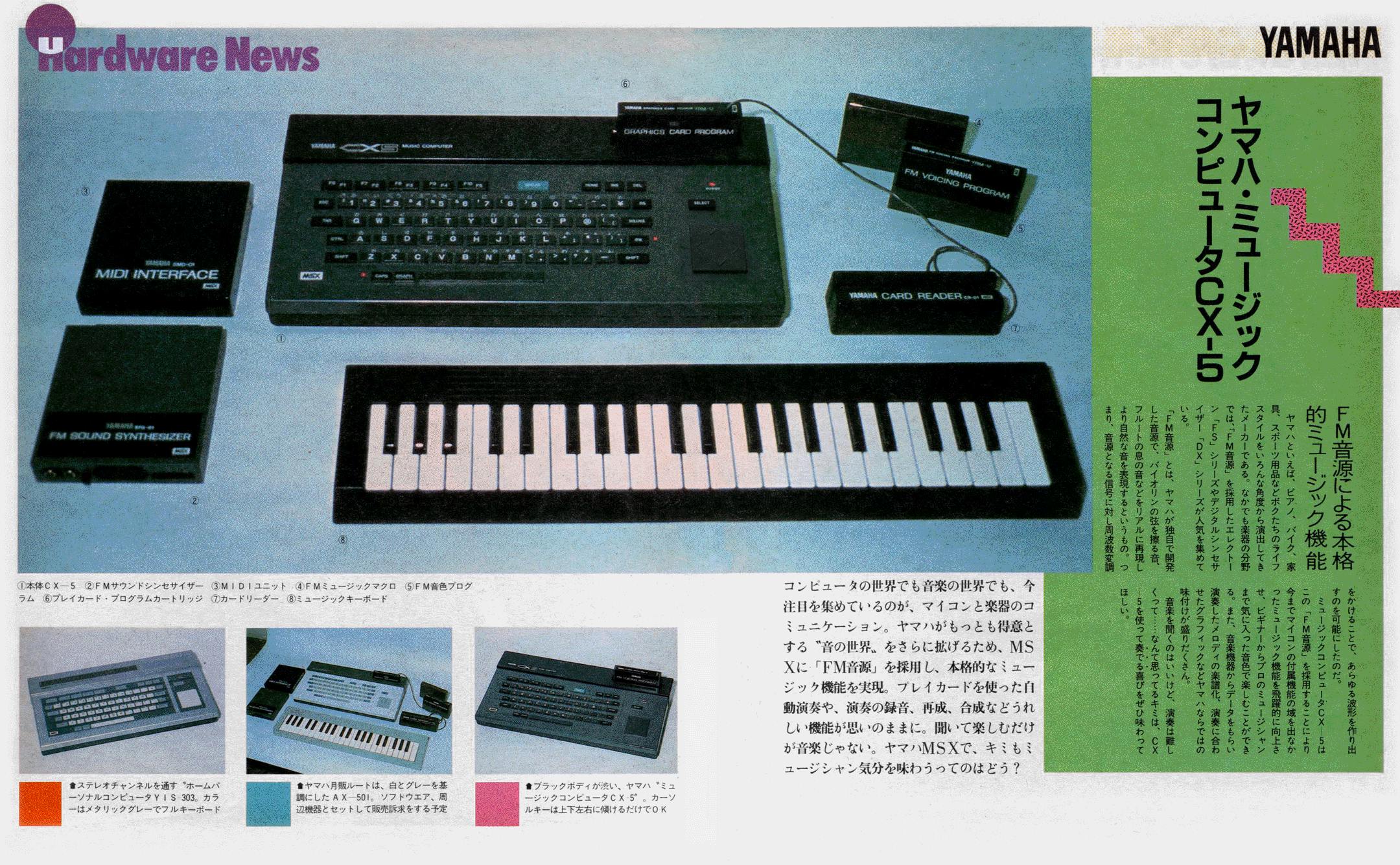

A "music keyboard" was also built, with a separate "music board" that had to be plugged into the central computer. The MK1 did in fact exist, and it was said to have a FM chip on board, but unlike other items it hasn't resurfaced yet in recent times. Could it be a prototype of the SFG01 ? After all, Yamaha had 6op and 4op FM chips ready for use in 1983, both in synthesizers and computers.

So it’s 1982, Yamaha had a big vision to bring together all their expertise in the music field and their will to enter the personal computer market, they had an innovative product with a clear technological edge on competitors, they set up stores around Japan, they had excellent advertisements and a decent press coverage even outside Japan. The price for a basic YIS bundle (PU1-10, monitor, keyboard, printer, wooden case for the monitor), however, was the highest in its category.

A basic configuration costed around 12.000$ in today’s money, with the PU1-20 bundle costing almost 15.000$. Accessories weren’t cheap either: around 3K for the piano experience or 2K for the synthesizer and music board. A lot of Japanese blogs now comment on these prices labeling the YIS as “too expensive”. While it’s true that it was double the price of an Apple II system and 4 times the cost of the NEC offerings, Yamaha’s computer also offered a lot more.

At the time of this article, a new Apple Mac Pro starts at 5.999$ which quickly jumps to 10.998$ when adding the Pro Display XDR. The most expensive configuration currently sits at around 55K dollars. It’s a machine aimed at professionals, people who do need that kind of computing power and are willing to pay some extra to get it in a fancy stainless steel enclosure. Yamaha’s product in 1982 wasn’t too different: it delivered game-changing features to scenarios where a difference between minutes and hours of computing meant real money, but could also appeal to people looking for a sophisticated design for their personal computer.

Yet today there’s hardly any trace of this system. No information on Yamaha’s website, it never pops up on auctions, nothing on the Internet in general except a couple of Japanese websites. What happened to the YIS (or “Wise” as it should have been pronounced)?

In May 1982 at Tokyo’s Microcomputer Show Yamaha presented a couple of cheaper alternatives to their central computer lineup: the PU10-D and PU10-S, which would have been priced at the same level as the Apple II. It’s unknown whether they actually reached market, but it could be considered as a hint of a long-term strategy to get a presence in the personal computer market at every price point (much like Yamaha will do with synthesizers a few years later).

However, January 1983 was the last time Yamaha had a YIS advertisement on ASCII magazine. Some of the last ones were actually repeated, like there wasn’t any more to say about the system. Why did Yamaha pulled the plug so quickly? How is it possible that the whole vision faded into obscurity in just one year? Did it really fail or could there be another explanation? This is just a speculation, but maybe a big change in management and MSX are the answers.

At some point in late 1982, it must have been clear to Yamaha’s then-president, Genichi Kawakami, that making a multimedia home computer with state-of-the-art sound and graphics capabilities was just too much for the company. Mochida’s error was pretending Yamaha could make processors, hardware, software, peripherals, and accessories while also continuing to invest in upgrading the manufacturing of components.

The DX7 was launched in Japan in May 1983. The dark chocolate materials used hint at some kind of integration with the original YIS ecosystem, but the digital synthesizer shipped with a very early implementation of the MIDI standard, and no traces could be found of an RS-232C connector (the one used across YIS products for interoperability). The DX1 even retained some of the wooden panels that would have looked great next to the other computer/furniture pieces. It’s possible to assume that by the time the DX7 came out Yamaha already scrapped the idea of continuing to invest in their own line of home computers.

At the same time, the “50.000 yen personal computer” market was booming in Japan: in December 1982 an NEC PC-6000 with a monitor could be bought for less than 90.000 yen, while other manufacturers were already rushing towards the 60K mark. Even if most computers shared similar flavors of BASIC, there was no compatibility between systems. This was true also abroad, especially in Europe. So when Microsoft tried to push for a standard for cheap home computers, which allowed for easy cross-compatibility, many manufactures jumped on board, including Yamaha.

So in late 1983, the first prototype of a “music computer” by Yamaha based on the MSX standard appears on the pages of “MSX Magazine”, the CX5 . Yamaha would abandon the in-house production of processors, focusing just on music-related chips (FM tone generators, DACs, MIDI interfaces). The YIS brand became just a small label on their MSX line of computers dedicated to the general public, such as the YIS303 and YIS503 , both on sale by the end of 1983. If the original YIS vision already looked like a burden to Yamaha, the adherence to the MSX standard was its final nail in the coffin.

This is also the year when Genichi retired, leaving the president role to its eldest son, Hiroshi Kawakami. Yamaha’s MSX computers had a discrete success, especially thanks to all the softwares that allowed programming synthesizers and drum machines directly from the computer, but it was not even close to the original dream of a multimedia computer, and again it wasn’t profitable either. Mochida recalls: “Within a year of commercializing the computer, I realized that we had made a mistake; So I went straight to Kawakami-san, and I told him that we should stop at once, that the more we did, the more money we would lose.” The 1986 YIS805 was Yamaha’s last MSX computer.

Allegedly there were plans for a Teletext terminal project, sponsored by the Japanese government, that had an FM chip on board, it’s unclear whether this would be related in any way to the YGT100 terminal. Excluding one last attempt at a PC-compatible laptop named C1, Yamaha switched to trying to sell sound chips to other computer manufacturers. The partnership with AdLib made Yamaha’s YM3812 chip very successful during the 1990s — but that’s another story.

Mochida was demoted from managing director to director, he suffered a cut in salary, and was re-assigned from his beloved R&D to run Yamaha's audio division. Today we can ask Siri to turn on the lights in our house and an AI-enabled camera can recognize whoever is ringing at the door — provided the wifi is still working. And yet Yamaha’s 1982 future must have been a great one to live.